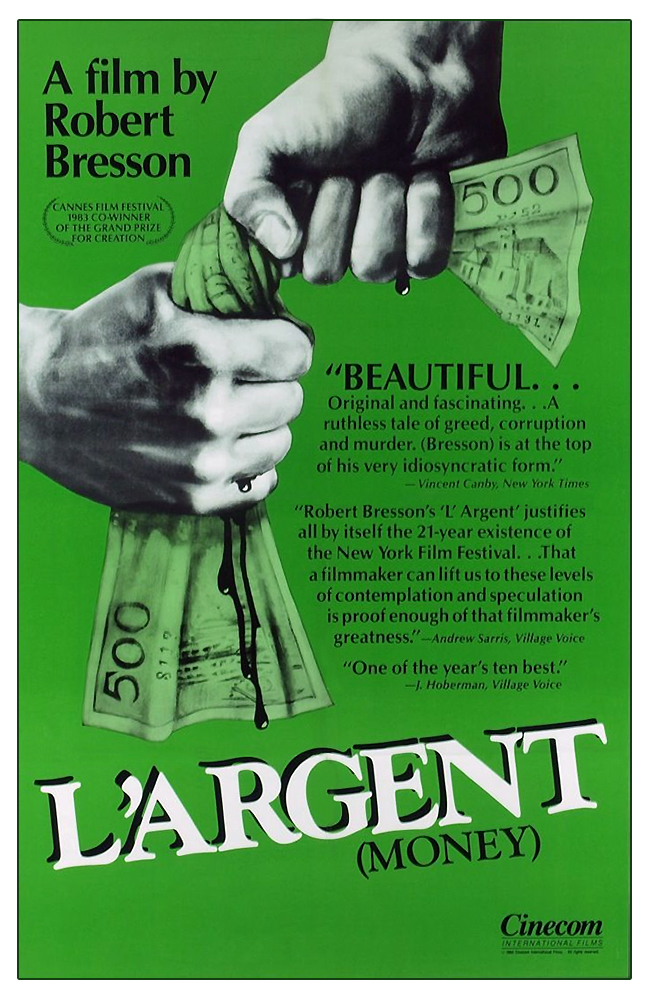

If film as an artistic medium is measurable by its effectiveness at visually expressing thoughts, concepts, emotions, and/or ideas, then you’d be hard-pressed to find a better purveyor of the form than Robert Bresson. His career as a filmmaker spanned almost fifty years and yet he only directed 13 feature films, garnering praise and renown from arthouse titans such as Andrei Tarkovsky, Jean-Luc Godard, and Francois Truffaut. His work is commonly described as minimalist and often features themes of small people trapped in a never-ending cycle of destruction, told with the barest of exposition and free of indulgence.

Simply put, Bresson’s films favor action over discourse; the “show” without the “tell”. If we can watch it happen, then words are superfluous. When stripped down to its most basic elements, storytelling is defined by the actions and choices of characters – everything else is filler.

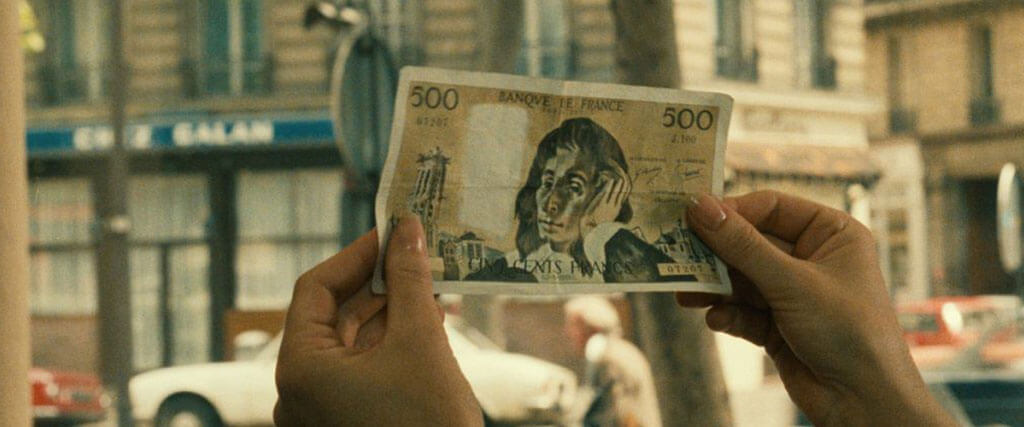

Such is the case with Bresson’s final feature, 1983’s L’ARGENT, which aptly translates to MONEY in English. The film begins with a schoolboy, Norbert, requesting a small sum of money to pay back his classmate. The request is denied by his father, and, in a state of duress, Norbert asks for a loan from a friend, who instead offers him three marginally convincing counterfeit 500-franc notes.

Without much consternation, the boys head to a local photo shop where they successfully pass the bills off, despite some questioning from the saleswoman. Later, the shop owner berates the saleswoman after discovering the blunder and subsequently decides the best course of action is to get rid of the bills, which unfortunately lands them in the hands of a local heating oil delivery man named Yvon. These conscious misdeeds proceed to ignite a disastrous series of events that tragically leads to acts of robbery, perjury, and murder.

The overarching theme is cause and effect, and the outward ripples of consequence that disseminate from the decisions we make. As a result of Norbert’s action, the shop owner and his staff act in desperation, and ultimately resort to the same criminal behavior they have just been a victim of. Yvon is subsequently arrested using the bills to pay his tab at a cafe, irrevocably altering the course of his life and the lives of his wife and child.

It’s undeniably tragic, but also, and surprisingly, emotionally sparse considering the subject matter. Bresson is economical in his filmmaking, which leaves no room for melodrama. You could watch his films without sound or any understanding of the dialogue and they’re just as effective. Why use a bunch of words when you have a camera telling the story?

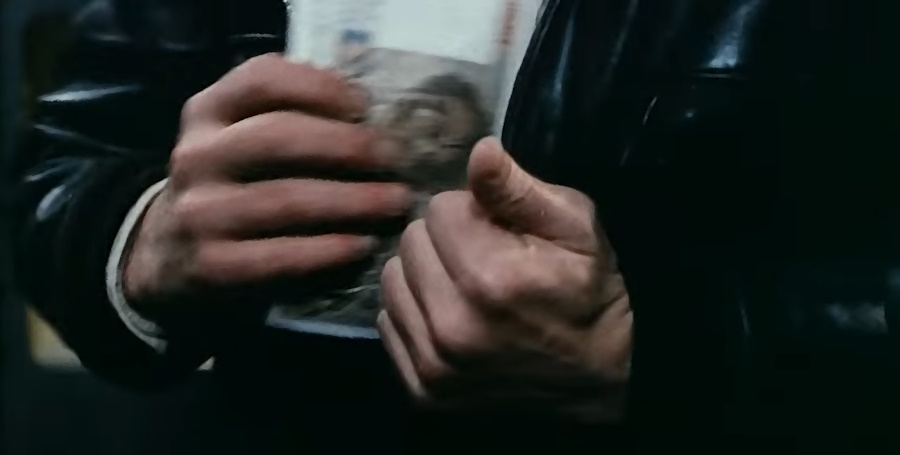

To wit, Bresson specifically focuses on hands throughout this film. This is common for many of his features, as evidenced by the theatrical posters for L’ARGENT, A MAN ESCAPED and PICKPOCKET. The ways people use their hands, and the tasks they use them for, are always at the forefront. Where most might conceptualize hands as symbols of comfort or friendliness, as in a protective hug or a welcoming handshake, Bresson portrays them as extensions of our greed (PICKPOCKET), brutality (AU HASARD BALTHAZAR), and dishonesty (L’ARGENT).

Though, in L’ARGENT, hands encompass nearly all of these traits. For this film, specifically, the transference of goods, services, and currency factors heavily into the narrative, and Bresson juxtaposes the imagery with acts of commerce and those of robbery, deception, and murder to take on the symbolic representation of this concept.

There’s a simple, but quietly suspenseful, scene that struck me in the latter half of the film that illustrates this point very well. At this moment Yvon is on his own, having lost his job, his home, his child, and his wife after being imprisoned. He’s standing on a city sidewalk, idly staring through a toy store window when a gray-haired woman walks past. They exchange glances and Yvon proceeds to follow the woman, keeping a safe distance behind her and only stopping when the woman and we, the audience, take a momentary detour into a bank to make a cash withdrawal.

Aside from the shift in perspective, what caught my attention is the banal energy to this whole scene. The woman walks up to the teller and slides the withdrawal slip across the counter. The teller processes the slip, counts and dispenses the cash, followed by the gray-haired woman collecting the bills, placing them neatly in her wallet, and exiting promptly. The scene lasts maybe a minute. Not a word of dialogue is spoken and nothing of consequence occurs during the transaction. Afterward, the action resumes with Yvon tailing the woman back to her home.

This begs the question: why did we follow her into the bank? The obvious reason is to establish the threat of Yvon harming and robbing the woman, but I don’t think that’s the sole reason. The mundanity of the scene is what sticks out to me. It’s both casual and business-like: hand in your ticket, sign the slip, collect your money, and get on with your day.

For me, the significance lies in the familiarity. It’s a deliberately cold scene that illustrates how financial institutions and systems have become a seamlessly integrated part of our lives. Both the woman and the teller have performed this same routine countless times, step for step. They’re aloof and lifeless in each other’s presence. The characters’ only interaction is with their hands: passing slips, signing forms, counting bills. Nothing else.

This scene is exponentially more true today where we see ATMs on every corner and in many stores, and can make bank transactions in an instant from our cell phones. So it continues to seep deeper and deeper into our lives. Money passes, invisibly, from one entity to the next, and from one hand to another.

In a sense, the bills are the protagonist for the first act, before ceding the stage to the fallout they’ve caused. Over the course of the film, the same honest, hard-working hands that once provided trusted services to the photo shop will cleanse their soiled palms of the blood of true innocents. This is how Bresson weaves his concepts into the visual motif as well the narrative action. We’re seeing the physical illustration of a figurative transference – the passing of debt, responsibility, and punishment from one character to another, and one social class to another.

To expand on that, I’d like to back up to where I left off on the plot description earlier. We’d witnessed two acts of fraudulent behavior, and the direct effect is clear. Norbert’s conniving scheme leads to the shop owner’s equal act of deception, which culminates with Yvon’s arrest. But the seeds of one misdeed bear much fruit, and the latter, the only innocent participant, bears the brunt of retribution from this point forward.

This film presents a unique case, wherein the cycle of crime is presented as a product of both our nature and the flawed socioeconomic and justice systems we’ve created. If we look at the three unrelated participants – Yvon, the photo shop staff, and Norbert – we see a multitude of classes, and in turn we see the various ways the wheels of justice spin for and against them.

Norbert comes from a place of privilege. He lives in a posh house and goes to an expensive school, no doubt an institution with an emphasis on manners and respect, and yet he doesn’t require much convincing to commit fraud. He’s also a spoiled brat. It turns out his monthly allowance, which isn’t as high as some of his friends, isn’t enough to cover his debt, so he turns to subterfuge without a thought of the harm it can do.

The first victim, the photo shop, has three participants of varying white collar classes. The saleswoman is lower-middle class. She’s skeptical of the boys, and yet, despite their awkwardness, she still accepts the bills. When confronted by the shop owner, she contends, “They looked honest”. No doubt their upper-class appearance had a hand in her willingness to trust them. Would she have given Yvon the same benefit of the doubt in his blue collar jumpsuit?

The boss, on the other hand, is a business owner and closer to the upper-middle class. He spots the fake bills right away, though the saleswoman points out that he accepted two similarly forged notes the previous week. From his standpoint, the decision to simply pass along the forged money is financially motivated. He’s in no criminal danger if he does nothing or turns the notes into the authorities. But if he doesn’t give the notes to someone else, he assumes the loss.

In the case of Norbert and the shop owner, their actions are purely self-serving. With little or no hesitation, they make their issue someone else’s problem, lest they suffer the consequences.

And if history has taught us nothing else, it’s taught us that there isn’t a problem created by the wealthy that the lower class won’t end up paying for. Because, what better target is there than the less fortunate?

Yvon presents the perfect opportunity to unload the money. He comes to the photo shop to deliver heating oil. He’s lower class and is likely uneducated, so he’ll never suspect the bills are phoney. Again, Bresson pays close attention to his hands; the sterile, drone-like movements as he caps the oil tank, notes the amount of oil, and fatefully opens the shop door. For Yvon, the ensuing tidal wave is completely unforeseen and unavoidable in the midst of the robotic mundanity of it all. He accepts their payment without question, because that’s how it’s always been. And when he’s confronted by the cafe staff he’s immediately deemed a criminal, no doubt aided by the mere fact that he’s still dressed in his work clothes, even as he calmly explains the logical reality of the situation.

The truth is, cause and effect are not weighed on a universal scale, and punishment is the great class differentiator.

The shop owner also employs his apprentice, Lucien, a wild card with a taste for expensive suits and a distaste for authority. He’s a character endowed with a certain amount of moral fluidity, and one who fluctuates between class identities. One moment he’s in court perjuring himself at his boss’s request, and then next he’s crudely scamming the shop with a rudimentary pricing scheme. He’s no more or less unscrupulous than Norbert and the shop owner, but his motives vary.

After being arrested, Yvon attempts to clear his name by confronting the photo shop staff. When approached, the shop owner defers to Lucien, who outright denies ever seeing Yvon before. This lie continues in court, where Lucien tells the judge the same thing.

In a “he-said-she-said” situation, what constitutes the mediator? It’s a battle of the “haves” and the “have nots”, where one is an upstanding business with an honest, clean-cut, working class apprentice and the other is a menial utility worker. The line of socioeconomic demarcation is practically visible in the courtroom. Yvon never had a chance.

So he stands silently in judgement, knowing his innocence, but powerless in the eyes of the law. The thunderous clap of judicial bias echoes throughout the courtroom. Naturally, Yvon is found responsible and forced to pay restitution, and ultimately loses his job.

Later outside the courtroom, as if to add insult to injury, the store owner rewards Lucien’s treachery with money for a nice suit he’s had his eye on. It seems they’ve landed on a transactional rate for a person’s livelihood.

Contrast this to the fate of the actual perpetrators of the crime.

Ultimately distraught at being fooled, the saleswoman pays a visit to Norbert’s school in an effort to unmask the culprit. The teacher poses the question to the class, but Norbert walks out in lieu of admitting his part in the crime. Later, his mother confronts the saleswoman at the photo shop and offers her a bribe to keep the matter quiet. As I’m sure you could guess, the bribe is accepted and in the end Norbert is grounded.

Once again, the scales of justice are proven to be unbalanced. Transaction complete.

Leave a comment