“I’d like to be a caretaker. To look after houses. Look after guard-dogs. There are so many big houses…so many rooms…”

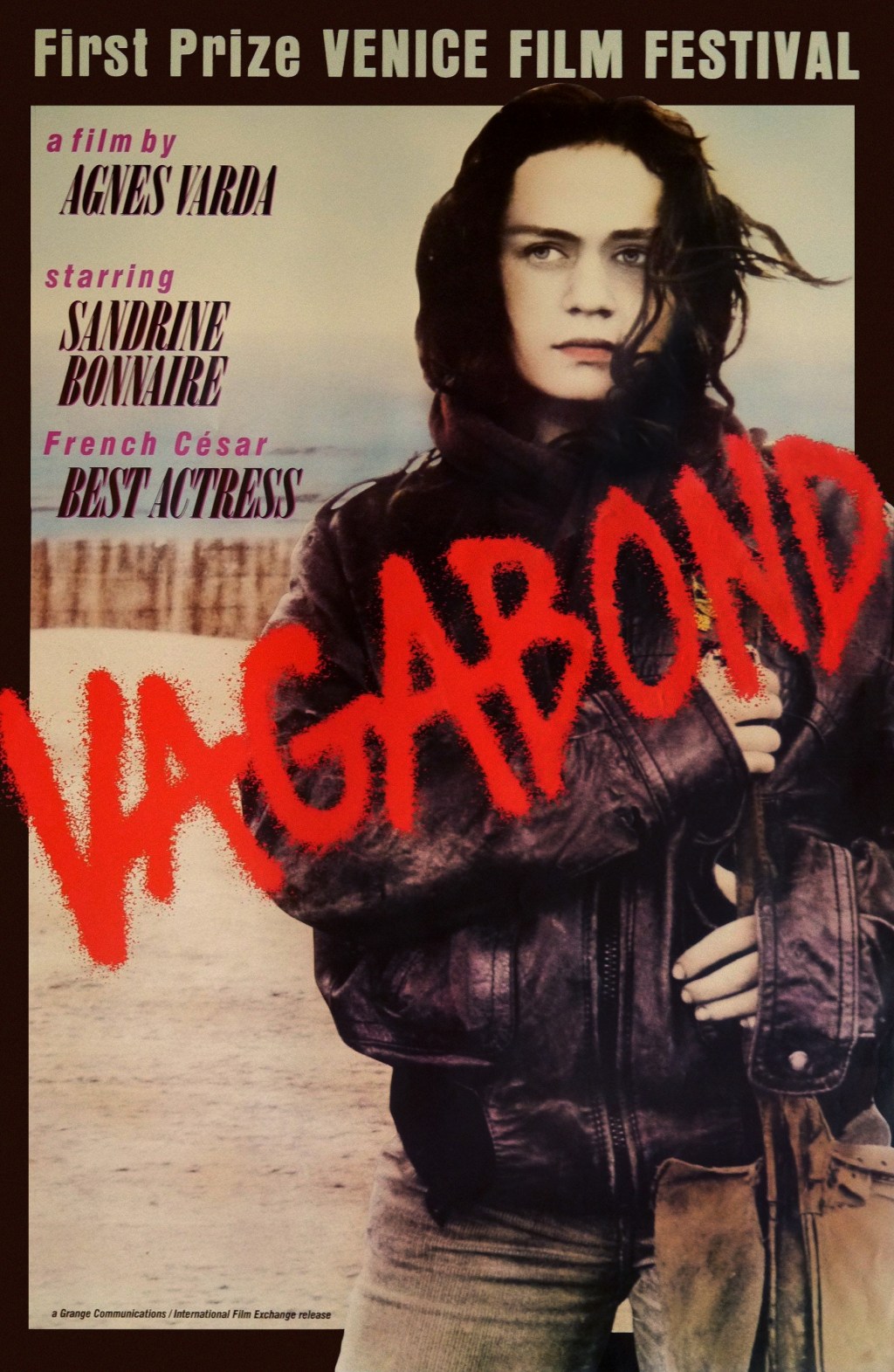

Emptiness, in all its forms, is ever present in Agnes Varda’s 1985 road *document, VAGABOND. The sentiment above is expressed by Mona, a young vagrant girl traveling the French countryside, during one of a series of random events in the last days of her life. It occurs in conversation after she meets a kindly middle-aged college professor, Mme. Landier, who previously suggested the unkempt wanderer would be better suited as a dog walker rather than a babysitter.

Such attitudes are common throughout the very brief time we spend with Mona, even among the most sympathetic of her temporary companions. She’s a drifter, in both the literal and figurative sense. The film begins as Mona’s dead body is discovered in a ditch, and from there it journeys backward, drifting, if you will, between particular moments in her life just prior to her death, with each segment documented by the strangers she interacted with.

Like memories we accumulate over time, some segments are short – maybe just a fleeting, momentary image – while others are rich experiences colored with vivid characters: trimming vines with a Tunisian man, a passionate, drug fueled fling with a like-minded squatter, a philosophical squabble with a family of goat herders, and a reckoning for a depressed maid who envies Mona’s freedom among them.

Still, the storytelling allows us minimal access to Mona’s history, and she isn’t always a sympathetic character. We get scant few details about her life, except that she was a secretary in Paris for a short period of time, but gave up that life to wander the land and be free of the rigid, systemic responsibilities.

But the objective here isn’t to give us a complete picture of Mona’s life. The strangers she meets represent many different walks of life, and the juxtaposition of the contrasting attitudes, lifestyles, classes, ethnicities, and ideologies creates an ongoing dialogue of differing perspectives on life, purpose, and the connections we make during our short time on this Earth.

I equate Mona’s existence to a work of art in the eyes of these strangers. They repeatedly question her purpose and meaning. Her nature is foreign and runs contrary to their way of life, and yet her existence is just as intentional and fulfilling as her traveling companion, despite what they might think.

There’s a lovely scene between interactions when Mona has set up her tent in a snowy field for a night. Her face emerges from inside as the cold morning breeze blows the flap of her tent open. It’s quiet and peaceful. She stretches her sleepy bones and scans the landscape, taking in the beauty of the panoramic view from her bedroom. She grins with satisfaction – where can you beat this view?

Yet to her acquaintances, the repugnant stranger they see before them represents a choice they could never make. One that requires a strong will, perseverance, and humility in order to survive. The goat farmer has a simple life, living off the land free of the constraints of society. But, he also opts to raise a family, something Mona sees as a hinderance. He postulates that Mona chose a lonely life, as she prefers to be alone, but he readily admits she is freer than he. He chose a middle ground, in deference to loneliness, because Mona’s journey ultimately ends in self-destruction.

But Mona chose her own path, too. And much the same way a work of art can affect us in emotional, psychological, political, and philosophical ways, whether we agree with what it represents or not, Mona leaves an imprint on these people. They can’t take their eyes off of her when she’s near, like a beautiful painting, and she remains in their thoughts long after she’s parted.

At the conclusion of the conversation alluded to above, the film transitions a short distance away to an abandoned house along the road. It’s surrounded by barren fields and appears empty and lifeless. We’re looking up the driveway at the boarded up windows and disheveled front yard, overgrown and beset with dead trees and a cold steel fence. It’s hard to imagine any warmth in this home, or that any pleasant memories were sealed inside when the final board was nailed in place.

This particular moment has stuck with me since I watched the film last week. The sadness of Mona’s words coupled with the rundown house creates such a feeling of yearning and regret. A building that at one time presumably housed a family, now bereft of life. So many empty rooms.

The scene then follows Mona and Mme. Landier down the road, as the latter explains that she’s working to save an entire species of trees, called plane trees, from being wiped out by a deadly fungus. The fungus, she says, behaves like a cancer, invading the trees and killing them slowly. Her goal is to create a strain resistant to the fungus before plane trees are completely eradicated.

Mona fidgets and listens while she talks, barely registering interest in her work. But she poses a pertinent question to Mme. Landier about her role with the diseased trees:

“You treat them?”

Mme. Landier, slightly taken aback, replies, “No, I’m an academic. College professor…” She pauses for some respectful acknowledgment, but doesn’t get it. Not satisfied with her answer, Mona responds, “So, who treats them?”

It’s basic and almost child-like, but this exchange further exemplifies the ideological and socioeconomic chasm between these characters. It’s a simple question, posed without condescension, yet it subtly undermines Mme. Landier’s role in saving an entire species of trees. But it also brings to light an interesting discussion about how we value life and the part we play in preserving it.

For these two characters, the term “preservation” evokes a very different connotation. The manpower, time, and resources from Mme. Landier’s projects are allocated to trees that aren’t planted yet, despite a suffering forest dwindling from cancerous decay in front of their eyes. Mona’s simple question highlights the immediate concern – who treats the forgotten trees rotting out in the cold, hungry, and slowly dying from the inside?

Even as preservation is often coupled with the noblest of intentions, it fails to account for the present. With eyes on the future, it’s hard to value what’s right in front of us, no? And by extension, how are we to determine our own value when the present seemingly has none?

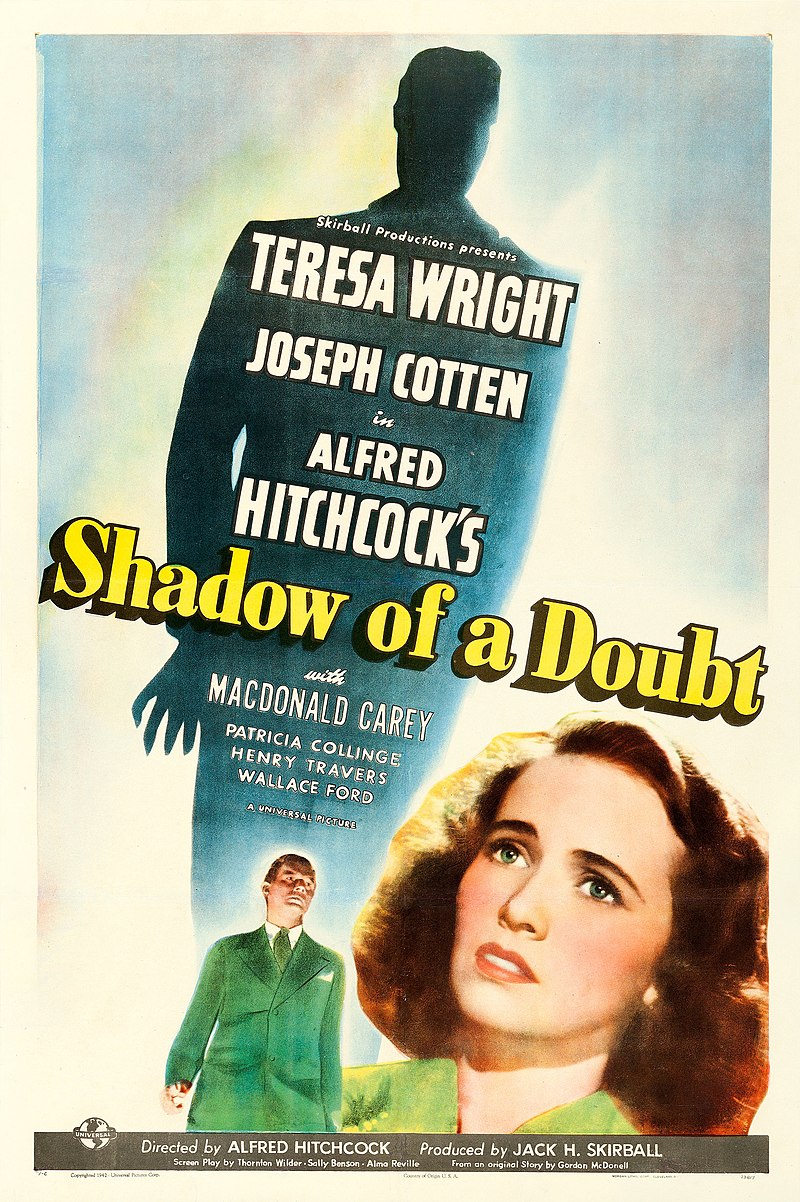

I can’t help but see a metaphor for middle-age malaise, the result of a banal world stuck in a materialistic value system. People work and plan for some eventual reward, building a future branch by branch, and brick by brick. The value, we’re supposed to believe, comes from putting in the work; from a lifetime of accumulation. If you don’t feel happy yet, don’t worry – you’ll get there.

So we stack our lives with jobs and causes to fulfill us along the journey, striving to consummate a promise of happiness with what we believe is our “purpose”, while the infection slowly eats at us from the inside.

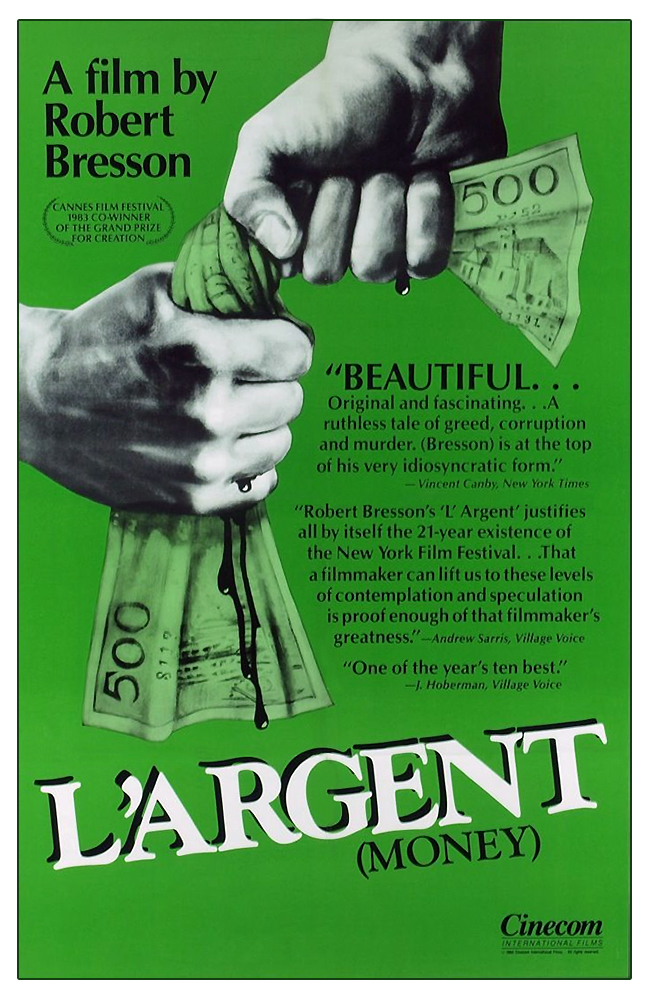

In a capitalistic system, hope and security are currency of the wealthy few. In their hands it becomes a weaponized ideology used to delude the working class into thinking they have a chance to rise above their status. The common result is insurmountable debt from trying to keep up with mortgages, student loans, credit cards, etc.

But don’t worry about all that, they say – just work a few extra hours, save your pennies, make some sacrifices, maybe take on a side job and a second mortgage, and you’ll get that class promotion! Oh and don’t forget to smile and keep up the good work!

Rinse, repeat.

What place does Mona, and what she represents, have in this world?

Mme. Landier spends a relatively significant amount of time with her. They talk about several subjects along the way and engage in some adolescent mischief when they share a bottle of champagne in the car, sans glasses. Shortly before this, Mona divulges that she did receive some formal education, but dropped out before she finished. This leaves Mme. Landier in shock, prompting her to ask why she would drop out. Mona responds with a gulp of bubbly and her indelible words:

“Champagne on the road’s better”

It leaves an impression Mme. Landier can’t shake immediately. In a society that deals in monetary currency, what quantifiable value can be placed on that? As a scientist working toward the idea of a better future, what value does the current world, and by extension Mona, have for her?

Despite her kind gestures and sympathy, Mme. Landier is just as dismissive of Mona as most of the others. As she recounts her thoughts after the fact, she can’t help but mention Mona’s “stench, her chain-smoking, her poverty…” In a world where societal value lies in the eye of the beholder – the homes we buy, the jobs we work, the clothes we wear – it begs the question, are you worth anything beyond the material in this world? Are we capable of acknowledging spiritual value?

I like to think of the film as a testament and appraisal of life. If you ask me, the film’s answer to these questions is, emphatically, yes and yes.

*Not a documentary, but the presentation and structure feel document-like

Leave a comment