The realization that your parents, or anyone in your immediate familial orbit (siblings, aunts, uncles) are flawed people, no matter which race, ethnicity, religion, political affiliation, or economic background you hail from, is something that eventually comes to us all. For some, it arrives tragically too soon. And for others it may come, mercifully or not, too late. Suddenly, and without warning, we’re face to face with the proverbial “original sin”; or perhaps the decomposing skeleton rotting in the closet. What’s worse – it comes from the place you least expect it. Lest we forget, from the nourishing riches of Eden came the poisoned apple that caused Adam and Eve to realize their shame and ugliness.

We can hope to be spared this fate until our golden years, when innocence has faded and time has eroded our memories down to scattered fragments, scarcely resembling either fact or fiction any more. But no matter when, the existential fork in the road arrives packing a seismic identity crisis. Or maybe in these consumer driven days we’d call it a “traumatic personal re-brand”, one in which our very foundation is shaken like a cosmic Etch-a-Sketch.

Being confronted with a horrible truth has far reaching consequences, no matter the circumstance. But it’s especially painful when that truth concerns a relative or close friend. It violates and skews our reality, reshaping what we thought we knew. Precious memories we held dear suddenly appear warped and corrupted, and we start asking questions we never asked before. Questions about people we never doubted before. People we thought we could trust implicitly because, after all, “they’re family”.

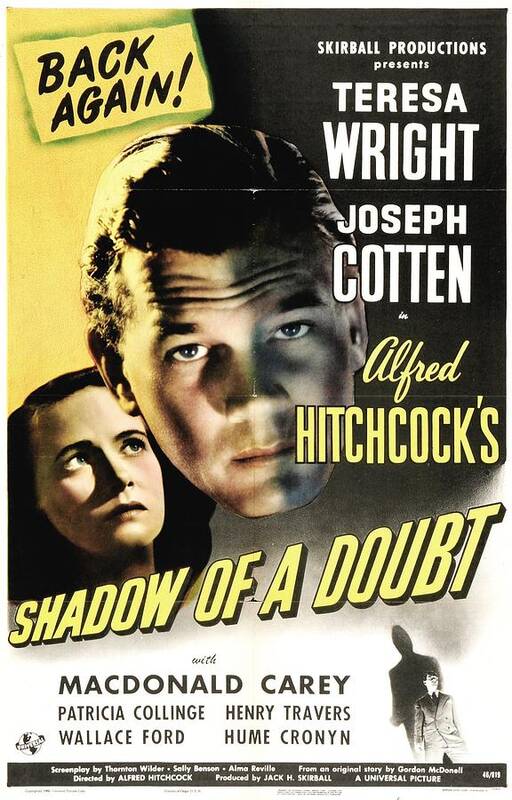

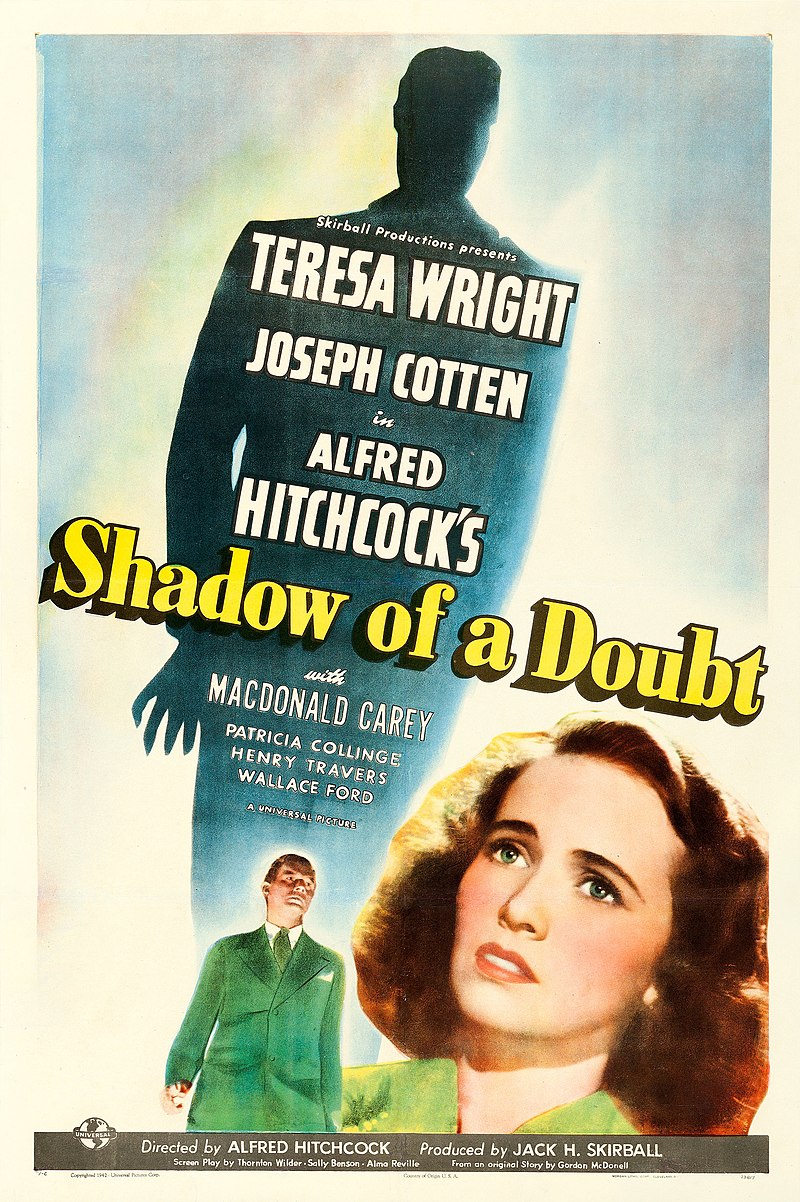

That formative occasion is at the core of Alfred Hitchcock’s 1943 noir thriller, SHADOW OF A DOUBT. The film, starring Teresa Wright and Joseph Cotten as a niece and uncle, seemingly simpatico since little Charlie Newton was blessed with her sweet Uncle Charlie Oakley’s name, is a dark coming-of-age tale wrapped in a mystery. More specifically, it’s a character mystery, one that effectively tests the bonds of a middle-class American family by questioning the moral fiber of the relationships we hold dearest.

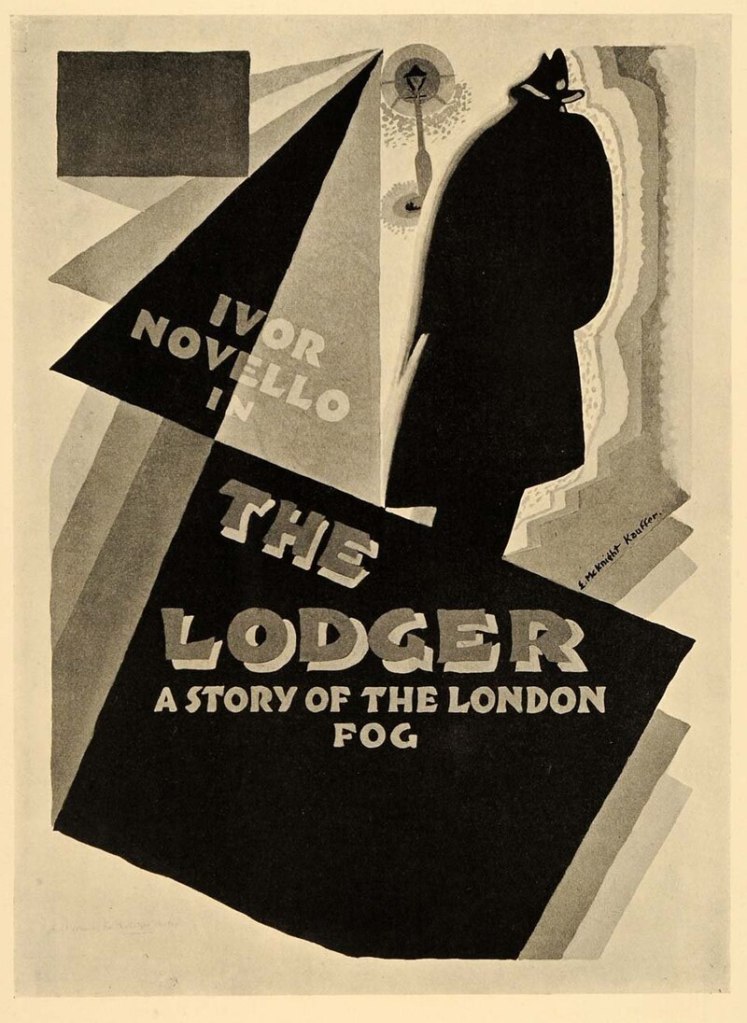

Almost all Hitchcock films are mysteries, but they’re often muddled and rarely, if ever, the mystery you think they are. To wit, I recently watched his final silent film, THE LODGER: A STORY OF THE LONDON FOG (1927), wherein a mysterious man takes up residence at a local boarding house in the midst of a string of serial killings in London. The frantic manhunt by the police, largely bumbling in their efforts to solve the case, eventually points to the stranger, who bears a striking resemblance to the physical description of the killer. As such, there is a dual mystery: who is this man, and is he the killer the police are looking for?

I bring this up because a similar mystery is at the center of SHADOW OF A DOUBT. Hitchcock, no doubt, has many well-known proclivities and is no stranger to mistaken identity narratives, but the addition of a psychological aspect is a demonstrable difference in the richness of the narrative between the two films.

SHADOW OF A DOUBT opens in Charlie Oakley’s hotel room in Newark, NJ, as he’s being informed that two men have come around looking for him. We don’t know the reason for his flight, but he manages to slip past his pursuers and send an impromptu telegram to his big sister across the country in Santa Rosa, CA – Uncle Charlie is coming for a visit! No one is more delighted at this news than his teenage niece, Charlie Newton, who adores her uncle and feels they have a special, unspoken connection.

Even though Uncle Charlie is blood related to these characters, we’re still dealing with the “mysterious stranger” narrative. Akin to the lodger, the family largely has no clue who he is or what he’s done. And the same goes for the audience. Both men arrive with opaque intentions, and if they are the killer then our main protagonists are certainly in danger. But instead of focusing on the crimes and procedural hunt for the killer, such as in THE LODGER, the film delves into the psychological danger of unmasking a potentially deadly character through the innocent eyes of young Charlie, who must decide (see also: accept) whether or not her beloved uncle is a cold blooded killer, and what to do about it if he is. Hitchcock, in essence, melds the two to create a thrilling and complex character study, leaving the fate of an entire hard-working family to a young girl’s moral judgement, while still answering the same two questions: who is this man, and is he a killer?

But SHADOW OF A DOUBT goes a little further, still, and poses a deeper question of young Charlie: what fate could befall the family if her uncle is the murderer?

We learn very early in the film that the family is middle class. They live in an average home with their three children, Charlie and her two younger siblings, Ann and Roger. Both parents work to make ends meet. Her father, Joe, works as a lowly bank teller and spends the evenings with his sheepish neighbor debating the most efficient and plausible way to kill one another and not get caught.

The family isn’t poor, per se, but it’s obvious we’re a far cry from the stately confines of Manderley. Nor is anyone getting swept off their feet by a tuxedoed spy with an Atlantic accent.

In short, life at the Newton household is simple and boring – and young Charlie can’t stand it anymore.

Enter Uncle Charlie, who appears to lead an exciting life and is a man of means. He also sees Santa Rosa as a quiet, boring place – which is perfect for laying low. Among his first priorities in Santa Rosa is to open an account at Joe’s bank – with a whopping $40,000. This, of course, is a shocking figure compared to the Newton family’s lesser means, proving Uncle Charlie to be a breath of fresh air for everyone, but especially young Charlie. After all, Uncle Charlie is traveling and living his life, meanwhile mother is still wearing her same old passé hat in public and trudging through the same routine, day in and day out.

While they may appear boring to Charlie, Hitchcock never presents the Newtons as anything but a loving family. They don’t have flashy toys or tell fascinating stories like Uncle Charlie, but there is warmth in the home, which is clearly disrupted by Uncle Charlie’s presence. The togetherness they shared before is fractured, and the strength of the family will be tested by their resistance, or lack thereof, to Uncle Charlie’s charm. Dare I ask, are we seeing a sentimental side to Hitchcock?

On the flip side, Uncle Charlie represents an element of danger, which undeniably attracts an adventurous spirit like young Charlie. Especially one on the verge of adulthood, looking for something bigger than small town life.

Again, by adding this depth to the story, Hitchcock takes the mystery and turns it into a character study. All of these variables must be factored in when young Charlie is presented with a choice. Contrasted to THE LODGER, wherein the thrilling climax features a quasi-anticlimactic reveal with the ever-present threat of physical danger, SHADOW OF A DOUBT not only threatens the life of a young girl, but also the livelihood of her entire family. By featuring a clear socio-economic delineation between the Newtons and Uncle Charlie, Hitchcock raises the stakes for her once more, now begging the question: what would happen to her family if Uncle Charlie is the murderer and they are of less than affluent means? Could they survive if mom and dad lost their jobs over this?

There are also familial and social pressures to factor in: what would happen to her mother’s well-being if she found out her baby brother is a cold-blooded murderer? What would their community think of them?

The gravity of these questions and the potential outcomes of her decisions have far reaching implications. The first, and likely most difficult, step is believing someone you look up to, trust, and adore could possibly do something as horrific as murder. Because you have to accept the difficult fact that you were very wrong about someone, consciously or not. It’s easy to make excuses in the moment and look the other way, even when all the signs are there, but you have to be willing to open your eyes.

Because, if I may say, Uncle Charlie is sketchy as hell. Sure, he’s charismatic and engaging while handing out presents to the family and loudly broadcasting to anyone within earshot the exact sum he’s depositing at the bank. But he also dodges every question about his recent whereabouts and things he’s done in the past, refuses to let himself be photographed, and rattles off cryptic monologues where he refers to old, rich widows as “wheezing animals”.

As the film continues, these moments mount and Uncle Charlie’s ball of yarn slowly starts coming unwound. It turns out there is a nationwide manhunt for a killer who murdered three wealthy widows, which is brought to young Charlie’s attention when two policemen knock on the Newton’s front door posing as census workers. As young Charlie develops more and more suspicions, she is forced to grapple with the potentially ugly truth about someone she cares deeply for.

And in the end, with everything in mind, she’s forced to answer the most difficult question: can she summon the courage to help the police and bring Uncle Charlie to justice, or does she help him make another getaway for the sake of her family, no matter the ramifications?

It’s all on the table. What would you do?

Leave a comment